HONG KONG HAS THE LEAST AFFORDABLE HOUSING MARKET, AND WHAT CAN BE DONE

While Hong Kong is highly ranked in GDP per capita, but there is a growing divide between affordable and substandard housing. Why Hong Kong is unequal and what can be done?

In this article, we will discuss key issues of housing market and some of the solutions that can be done by the government and property developers.

As part of their efforts to promote social entrepreneurship, SOW Asia and HKUST are inviting submission from HKUST community of immediate or short-term solutions in the form of products, projects and/or services that could address the housing issues faced by those living in subdivided flats / units and cage homes in the HKSAR.

Context / Why are we where we are today?

Hong Kong remains as the world’s least affordable housing market for the 11th year, underscoring the income disparity in the financial hub.

According to a recent Our Hong Kong Foundation research, 300,000 flats are required by 2025 to meet the necessary demand – however, it’s unlikely that the demand / target will be met based on the current pace of construction.

The Government is trying to eradicate sub-divided housing by 2049. Housing cost commands a significant premium as land is controlled by the government, and is auctioned by government to private companies – Hong Kong is relatively less developed than other major cities in its land usage (about 25% of total land area of 1,110km2 (430 miles2) has been developed).

The poverty rate in Hong Kong was 21.4%, according to the 2019 Poverty Situation Report. More than 1.4m Hong Kong residents live below the poverty line (HK$21,400 per month for a family of four). Hong Kong has one of the widest wealth gaps in the developed world.

It is taking longer for residents of Hong Kong to get into public housing (c.28% of Hong Kong population lives in public housing). They can currently expect to wait 6 years before getting an apartment as at June 2022 (following a peak of 6.1 years, the longest since 1998). As of the end of June, there were about 144,200 general applications for public housing, while there were also about 98,400 non-elderly one-person applications under the quota and points system - many of whom also do not receive any support from family or are eligible for Government support measures (e.g. cash allowance introduced in June 2021).

The requirements for living in Hong Kong’s public housing are extremely stringent and even for those who are eligible face obstacles when seeking housing. Public rental housing (“PRH”) in Hong Kong is distributed across four districts: primary urban area, extended urban area, new territories, and outer islands. In order to gain a spot on the PRH waitlist, applicants must have seven years of residency in Hong Kong and their income cannot exceed an amount set by the Hong Kong Housing Authority at any time during the application period. For example, the income for a family of four applying for PRH cannot exceed HK$26,690 (USD$3,400) and they can be removed from the waitlist if their income fluctuates. Not only does this policy restricts recent immigrants from mainland China, who had prompted the creation of the PRH system, but it also places applicants in a precarious financial position where they are de-incentivized from increasing their income in order to maintain a spot on the waitlist.

According to the 2021 Long-term Housing Strategy annual progress report by the Housing Bureau, there are currently 127,100 households living in substandard housing1 in Hong Kong (of which c.92,2000 are living in SDUs or subdivided units), an increase of 12,000 households over the past four years. Many face the problem of rising rent, and suffer mental stress from the pressure of trying to make ends meet.

More than 60% of SDUs are in Kowloon, about 24% are in the New Territories, and the rest are on Hong Kong Island. Households tend to be small, averaging two people. The majority of units, some 82%, are in buildings that are 50 years or older.

Almost a third of surveyed SDU households by Habitat Humanity have reported paying 50% of their income to rent.

On top of that, cage homes and subdivided housing are usually located in buildings with structural problems, fire safety issues, serious water seepage and/or pest infestations. The living and hygiene conditions are appalling.

Interestingly, Singapore, which is similarly over-populated with limited land, has not witnessed a surge in SDUs.

According to World Economic Forum, access to affordable housing has major links to other major societal and environmental issues, and it is therefore an imperative to help to solve and realize the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations Foundation.

Key issues / pain points, and what are some of the solutions?

There are three key aspects that need to be addressed in the longer term to help with affordable housing, being (1) soaring property prices and a lack of affordability for middle- and low-income residents; (2) insufficient supply of public rental flats for grass-roots residents; and (3) very limited housing options for residents who are waiting for public housing2.

Affordability: Rent psf is actually higher for SDU compared with that for a normal rental apartment in HK. Expediting construction of PRH to house more people and shortening the waiting period will surely ameliorate issues of affordability in the long run. Statistics show that in April 2022, the average monthly rent psf of a private flat under 430 sq ft was about HK$37 on Hong Kong Island, HK$35 in Kowloon and HK$28 in the New Territories. For SDUs, the median monthly rent – the midpoint between the lowest and highest rents – was HK$39 psf, according to the report by the Transport and Housing Bureau. A 2017 survey by the Kwai Chung Subdivided Flat Residents Alliance found the average living space per person was only 50 sq ft in SDU – roughly the size of three toilet cubicles or half the size of a standard parking space. Prisoners in shared dormitories have an average space of 49.5 sq ft per person, while maximum security prisoners typically get 75 sq ft of living space.

Inefficient supply: Demand significantly outpaces supply (even with the new units being built) – especially as previous policies in the early 2000s focused on the shift towards private housing market. There are numerous measures which the Government needs to take to increase supply over the coming years.

Transitional Housing: Transitional housing provides residents on the waitlist for public housing with affordable shelter, but the tenure period of two to three years is short and fails to align with the average wait time for accessing PRH. Eligibility criteria for transitional housing are also high.

The Government has tried to alleviate the cost burden for SDU residents, through the introduction of the Tenancy Control Ordinance for Subdivided Flats which came into effect on 2 January 2022, whereby landlords cannot increase rent within a two-year period and only hike rent by no more than 20% after two years, as well as making it illegal for landlords to overcharge for water and electricity. However, the enforcement of the ordinance (i.e. inspections) has been lacking thus far due to Covid-19 restrictions during the 5th wave.

In addition to the high rent, there are other aspects that lead to even more expenses being incurred by residents, leading to additional financial burden:

Many times, residents often bear large out-of-pocket expenses for maintenance / repair of their units despite landlord’s obligations under the Tenancy Control Ordinance for proper maintenance and repair for drains, pipes, and electrical wiring, fixtures and fittings. Results of a survey by the Concerning Grassroots Housing Association in May 2022 suggested that only 40% of owners have committed – in writing or verbally – to take responsibility for such maintenance and repair – leaving the onus to tenants to restore / pay out of pocket of any of this.

Cost of utilities - Despite the Tenancy Control Ordinance for Subdivided Flats coming into force to prevent landlords from overcharging tenants of SDUs for utilities, many said the situation has not improved – where landlords often provide a figure without evidence of usage / actual fees the landlords are paying for utilities as many residents are often forced to share a water meter with their fellow tenants and do not receive separate bills. Such living conditions allow landlords or principal tenants to decide the amount that each occupant pays. The Water Supplies Department stated that it had received 20 reports of overcharging between May 2021 and January 2022 and none of the cases had been prosecuted. Furthermore, residents did not know about the ban on overcharging of utilities, whereas others may also be afraid to report their landlord.

Living conditions are usually harsh, including leaky floors, poor ventilation and fire safety hazards. As a result of the poor design of these structures, residents often experience indoor conditions that can be 5 to 6 degrees Celsius hotter than outdoors during a heat wave. More details and recommendations can be found through recent policy response by Habitat for Humanity3.

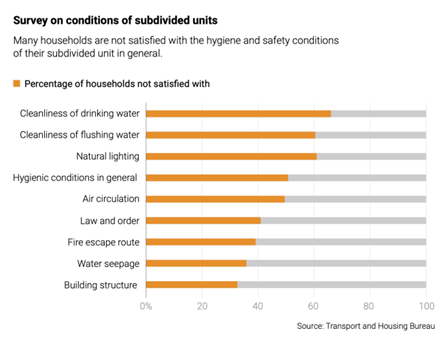

Key concerns based on Transport Bureau Survey in 2021 are as follows

Cleanliness of drinking water / flushing water: Owners of SDUs often add toilets and branch sewage pipes without the consent of the corporation, and connect them to vertical public drainage pipes without permission. The branch pipes installed on the outer wall and connected to the vertical drainage pipes from the kitchen and toilet facilities in individual units are for the exclusive use of individual units. The maintenance and repair are the responsibility of the owners of the relevant units. Unfortunately, not all owners would pay attention to the problems. Someone using the water to bathe and cook, and the sewage will flow to the pipes of different units. It is smelly and affects a lot of residents in other units. Also, the connection points of the pipes are prone to aging and loosening, so the chance of leakage is high. This leads to major hygiene issues.

Natural sunlight: According to a report released in July 2021 by Concerning Grassroots' Housing Rights Alliance (the “Alliance”), a non-governmental organisation, nearly 20% of tenants of SDUs either do not have or cannot use windows. Of the remaining tenants, only 36.5% have access to one window.

Air circulation: Visits by the Alliance found that 47.6% of the SDUs had temperature readings of above 30 degrees Celsius. Going by medical research stating that 24 degrees Celsius is the optimal room temperature for humans, the indoor temperature of SDUs is unsuitable for humans to live in. The report also stated that, because of the warm weather, nearly 50% of respondents were unwilling to stay home due to worsening living conditions and increasing mental stress. According to a recent Oxfam study4, nearly 70% respondents said that the intense heat affected their everyday lives, especially their physical health. They also found it difficult to work/study, and experienced more stress. Nearly a quarter of respondents added that with the heat, they saw an increase in mosquitoes and rodents. Two interviewees had experienced heatstroke, and one of them even had heat cramps5.

a) As part of the Oxfam study, Chan Ka Hing, who specialises in social design, recommended using raised floors to add storage space in SDUs and using insulation panels to reduce indoor temperatures.

b) Other solutions could include to partner with storage companies to temporarily place residents’ items in storage units, thereby increasing the amount of space in their flats and improving their living conditions.

Hygiene issues: Many SDUs have rats, mosquitoes and bugs. Many units have a makeshift kitchen installed in the living room or a bedroom. More than half share a toilet with 7 to 10 others – with some using the same toilet with as many as 16 to 20 others – and there were complaints that common areas such as the kitchen and bathroom were not cleaned during the pandemic. Toilet areas without natural ventilation are at risk of accumulating germs or viruses, a health risk made more imminent in the restricted space of SDUs, where germs can more easily spread to living or cooking areas. Rubbish collection is irregular or lacking and maintenance of collection areas is lax, worsening pest infestations and unhygienic condition.

Water Seepage: Wrongly connected water pipes smell bad, and water seep through walls or from the ceiling.

Structural issues leading to hazard: Some partitions are not fire-resistant and, without access to kitchen facilities, cooking over an open flame within the units is a fire hazard. The Buildings Department warns that work to remove original walls and install new partitions to create SDUs or add toilets and kitchens may adversely affect safety and hygiene, and put tenants’ lives at risk.

As a result, many of the residents often suffer from mental health issues. According to a survey conducted by Caritas’ Youth and Community Service division and Health In Action between March 2021 and April 20226, c. 80% of respondents suffered from insomnia, while more than 40% of them showed a high probability of depression or anxiety. Another survey conducted in Kwai Chung Subdivided Flats Resident Alliance suggests a number closer to 73%.

Because of the conditions that residents are in, there is a lack of sense of community / belonging as often they feel inferior to those in society.

Inequality in treatment towards SDU residents has been observed, especially for minorities / immigrants to Hong Kong

Prospective tenants are refused rental flats on the basis of the passport they hold. Against this discriminatory behaviour those seeking housing have little recourse, as this behaviour is not against the law. Real estate agents often propagate the situation by cooperating with landlords.

What are some of the longer-term government actions to address housing issues?

Development of the Northern Metropolis – this will eventually provide homes for as many as 2.5m residents (c.1/3 of the city’s population)

Government department has now split the previous Transport and Housing Bureau into two, creating a Housing Bureau dedicated to property issues – to support the focus on specific issues.

Under John Lee, two task forces have been set up to resolve housing issues, and they have pledged to submit reports on land supply forecasts and measures to speed up the construction of public flats by end of September 2022.

Other recommendations from various sources include:

The Government should do more in terms of participation in market place – e.g. it sells many parcels of land, but rarely does it repurchase buildings from private markets, as a means to support its ability to provide housing that maximises cost effectiveness.

The Government is already starting to construct buildings with more green materials – which helps the longer term strategy of cost effectiveness (e.g. more affordable housing).

To increase public housing supply, the Government can look to start by streamlining the approval process for land and housing development, and to reduce the time required for land development, environmental assessment and writing reports. The establishment of a task force on public housing projects, could expedite the completion of public flats over the next five years.

What are some of the real estate developers doing?

New World for Good (launched by New World) – It will research into long-standing housing issues, ranging from unaffordable prices, long waiting times for public housing and a lack of elderly-friendly homes as the population ages.

New World – unveiled a plan to offer 300 homes at about half of their market price in December 2021, becoming the first private-sector developer to subsidize housing in the city.

Henderson Land and Sun Hung Kai - They have voluntarily donated land for social housing and are participating in the Government’s public-private land sharing program.

Hongkong Land – It launched a new programme backed by a HK$100 million (US$12.84 million) fund aimed at helping 1,000 pupils and their families living in SDUs to climb the social ladder. The fund will offer educational and counselling programmes to 1,000 Primary Four to Form Six students and their families stuck in cramped spaces in Yau Tsim Mon and Sham Shui Po districts, two of the poorest areas in Hong Kong.

1 Defined as households living in units made up of temporary structures, households living in non-residential buildings, households sharing the same unit with other households, and households living in SDUs. https://www.hb.gov.hk/eng/policy/housing/policy/lths/LTHS_Annual_Progress_Report_2021.pdf

3 https://habitat.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Beyond-Four-Walls-and-a-Roof-6.13.22.pdf

4 https://habitat.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Beyond-Four-Walls-and-a-Roof-6.13.22.pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to express our appreciation to Elena Kan, one of our business volunteers, who worked diligently to summarize her research and let us have a better understanding of the housing situation and issues in Hong Kong as of October 2022.

2022 SOW (Asia) Foundation Limited. All rights reserved.